For years, Millicent McKinnon of Dallas went without health insurance. She was one of roughly 1 million Texans who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid in the state but too little to buy their own insurance. That is, until she died in 2019. She was 64 and had been unable to find consistent care for her breast cancer.

Lorraine Birabil, McKinnon’s daughter-in-law, said she is still grieving that loss.

“She was such a vibrant woman,” she said. “Just always full of energy and joy.”

Health insurance for roughly 2.2 million Americans is on the table as Congress considers a spending bill that could be as high as $3.5 trillion over the next decade.

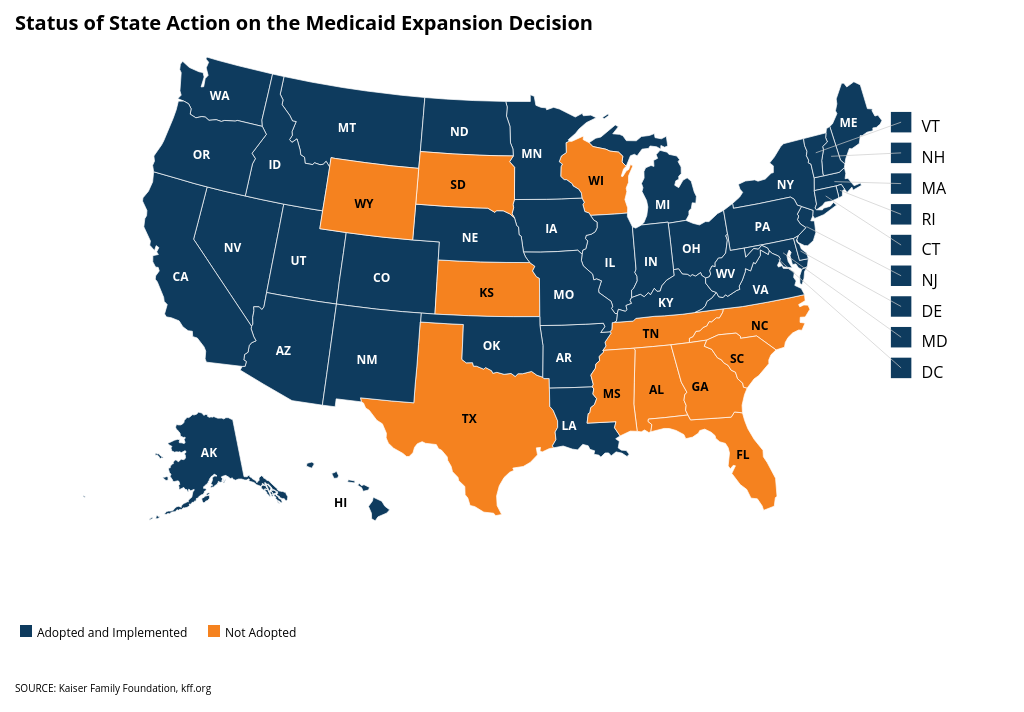

This plan would extend health coverage to residents of the 12 states that have yet to expand Medicaid to their working poor through the Affordable Care Act. In those states, people who earn too little to qualify for Medicaid — but who can’t afford to buy insurance in the individual marketplace — are left in what’s referred to as the Medicaid gap. Like McKinnon, most of these people work in jobs that don’t offer affordable health insurance.

If Congress approves the measure, those individuals would have access to a health plan through the federal government.

This could be a lifeline to some of the 17.5% of Texans who are uninsured, the highest rate in the country.

McKinnon was a descendant of runaway slaves who settled in Chicago. As an adult, she moved to Dallas and worked in health care her entire career. Her last job was as a home health aide, taking care of the elderly and people with disabilities. Birabil said she didn’t make a lot of money, though, and didn’t get health insurance.

And that’s why, when McKinnon started feeling sick, she put off going to the doctor.

“She didn’t have the coverage,” said Birabil, a lawyer who served briefly in the Texas House of Representatives. “She was doing everything she could do to live a healthy lifestyle. And so, when she realized that something was wrong and she went to find out what it was, it turned out that it was stage 4 breast cancer.”

In the year after her diagnosis, she bounced around hospitals. Doctors would stabilize her and send her home. Without coverage, consistent treatment was hard to find. Her family looked for insurance but found nothing.

All they could do in the end was be there as she slowly died.

“At the time that we found out, you know, we were also pregnant,” Birabil said. “And she kept saying, ‘I just want to meet my grandbaby.’ And she didn’t make it.”

A month before her granddaughter was born, McKinnon died. She was months away from getting Medicare.

Birabil said the health care system her mother-in-law spent her life working in ultimately failed her.

Laura Guerra-Cardus, deputy director of the Children’s Defense Fund in Texas, said advocates like her have been pleading with state lawmakers for years to cover uninsured Texans.

“But purely political opposition from our highest leaders, the governor and the lieutenant governor,” she said, “is enough to block progress on an issue that is a basic right.”

That’s why Guerra-Cardus, and other health care advocates across the country, are now looking to President Joe Biden and Congress to fix this problem. The Democrats’ $3.5 trillion spending bill — Biden’s “human infrastructure” bill — includes money to cover the uninsured via the health insurance marketplace and state Medicaid programs.

Most of those who would benefit are people of color in the South.

“We are asking them to choose to make America a country that does not block health care from anybody,” Guerra-Cardus said.

The racial disparity is stark in Texas, where about 70% of people in the coverage gap are Latino or Black.

Jesse Cross-Call with the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities said this is the first time since the Affordable Care Act went into effect that Congress may have enough votes to address this issue.

“This really is the unfinished work of the ACA to ensure that everybody in this country who is poor or of moderate incomes has access to affordable health care coverage,” he said.

But this insurance lifeline is competing for money and attention with other priorities.

Politico reported that this plan could be curtailed as Democrats negotiate a trimmed-down version of the spending bill.

For example, some lawmakers have suggested they would be willing to scale back health coverage for people in the Medicaid gap to just five years.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas), chair of the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, said in a statement Tuesday that Congress “must permanently close this coverage gap” so people in the 12 Republican-controlled states are never again denied health care.

“Closing the coverage gap means getting access to a family physician, essential medicines and other health care for [millions] who have been left out and left behind for more than a decade,” he said.

Some Democrats have also raised political concerns that extending coverage in non-expansion states would reward the Republican leaders in those states that have blocked Medicaid expansion for years.

Guerra-Cardus said that argument “is so far from the point” when it comes to why Congress should address the coverage gap.

“This is about people who are dying and suffering from preventable, treatable illnesses in the 21st century in our rich country,” she said.

In every state where Medicaid expansion has been put on a ballot, it has been approved by voters, most recently in Oklahoma and Missouri.

This story is part of a partnership that includes KUT, NPR and KHN.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.